Portuguese India

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

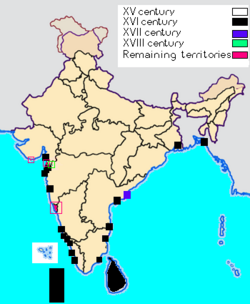

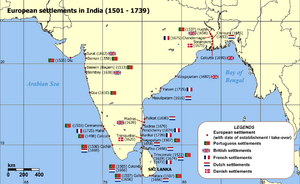

Portuguese India (Portuguese: Índia Portuguesa or Estado da Índia) was the aggregate of Portugal's colonial holdings in India.

The government started in 1505, six years after the discovery of sea route to India by Vasco da Gama, with the nomination of the first Viceroy Francisco de Almeida, then settled at Kochi. Until 1752, the name "India" included all Portuguese possessions in the Indian Ocean, from southern Africa to Southeast Asia, governed - either by a Viceroy or Governor - from its headquarters, established in Goa since 1510. In 1752 Mozambique got its own government and in 1844 the Portuguese Government of India stopped administering the territory of Macau, Solor and Timor, being then confined to Malabar.

At the time of British India's independence in 1947, Portuguese India included a number of enclaves on India's western coast, including Goa proper, as well as the coastal enclaves of Daman (Port: Damão) and Diu, and the enclaves of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, which lie inland from Daman. The territories of Portuguese India were sometimes referred to collectively as Goa. Portugal lost the last two enclaves in 1954, and finally the remaining three in December 1961, when they were occupied by India (although Portugal only recognized the annexation in 1975, after the Carnation Revolution and the fall of the Estado Novo regime).

Contents |

Early history

Vasco da Gama (1498)

The first Portuguese encounter with India was on May 20, 1498 when Vasco da Gama landed in Calicut (Kozhikode) in the present-day Indian state of Kerala. Over the objections of Arab merchants, Gama managed to secure a letter of concession for trading rights from the Zamorin, Calicut's local ruler. Unable to pay the prescribed customs duties (that Gama sought to be waived) and price of his goods in gold[1] (as was the practice then), the King's officials detained Gama's Portuguese agents as security for payment (who were released later). This however annoyed Gama, who carried a few Nairs and sixteen Mukkuva fishermen with him by force[2]. Nevertheless, Gama's expedition was successful beyond all reasonable expectation bringing in cargo that was sixty times the cost of the expedition.

Pedro Álvares Cabral (1500-01)

Pedro Álvares Cabral sailed to India, discovering Brazil on the way, to trade for pepper and other spices, establishing a factory at Calicut, where he arrived on 13 September 1500. In Cochin and Cannanore Cabral succeeded in making advantageous treaties. At Calicut this however precipitated matters with the Arabs. Matters worsened when Cabral notoriously captured several vessels at the port and massacred the crew which was retaliated by the locals who burned down the factory and butchered several Portuguese. Cabral started on the return voyage on 16 January 1501. He arrived in Portugal with only 4 of 13 ships on 23 June 1501.

Gama sailed the second time to India with 15 ships and 800 men and arrived at Calicut on October 30, 1502, where the Zamorin was willing to sign a treaty. Gama this time made a preposterous call to expel all Muslims from Calicut which was vehemently turned down. He bombarded the city and captured several rice vessels and barbariously cut off the crew's hands, ears and noses[3]. He returned to Portugal in September 1503.

Francisco de Almeida (1505-09)

On 25 March 1505, Francisco de Almeida was appointed Viceroy of India, on the condition that he would set up four forts on the southwestern Indian coast: at Anjediva Island, Cannanore, Cochin and Quilon.[4] Francisco de Almeida left Portugal with a fleet of 22 vessels with 1,500 men.[4]

On 13 September, Francisco de Almeida reached Anjadip Island, where he immediately started the construction of Fort Anjediva.[4] On 23 October, he started, with the permission of the friendly ruler Kōlattiri, the building of St. Angelo Fort in Cannanore, leaving Lourenço de Brito in charge with 150 men and two ships.[4]

Francisco de Almeida then reached Cochin in 31 October 1505 with only 8 vessels left.[4] There he learned that the Portuguese traders at Quilon had been killed. He decided to send his son Lourenço de Almeida with 6 ships, who destroyed 27 Calicut vessels in the harbor of Quilon.[4] Almeida took up residence in Cochin. He strengthened the Portuguese fortifications of Fort Manuel on Cochin.

The Zamorin of Calicut prepared a large fleet of 200 ships to oppose the Portuguese, but in March 1506 Lourenço de Almeida (son of Francisco de Almeida)was victorious in a sea battle at the entrance to the harbor of Cannanore, the Battle of Cannanore (1506), an important setback for the fleet of the Zamorin. Hereupon Lourenço de Almeida explored the coastal waters southwards to Colombo, modern Sri Lanka. In Cannanore however, a new ruler, hostile to the Portuguese and friendly with the samorin, attacked the Portuguese garrison, leading to the Siege of Cannanore (1507).

In 1507 Almeida's mission was strengthened by the arrival of Tristão da Cunha's squadron. Afonso de Albuquerque's squadron had however split from that of Cunha off east Africa and was independently conquering territories to the west.

In March 1508 a Portuguese squadron under command of Lourenço de Almeida was attacked by a combined Mameluk Egyptian and Gujarat Sultanate fleet at Chaul and Dabul respectively, lead by admirals Mirocem and Meliqueaz in the Battle of Chaul (1508). Lourenço de Almeida lost his life after a fierce fight in this battle. Mamluk-Indian resistance would be decisively defeated however at the Battle of Diu (1509).

Afonso de Albuquerque (1509-1515)

In the year 1509, Afonso de Albuquerque was appointed the second Viceroy of the Portuguese possessions in the East. A new fleet under Marshall Cutinho arrived with specific instructions to destroy the power of Calicut. The Zamorin's palace was captured and destroyed and the city was set on fire. But the King's forces rallied fast to kill Marshall Cutinho and wounded Albuquerque. Albuquerque nevertheless was clever enough to patch up his quarrel and entered into a treaty with the Zamorin in 1513 to protect Portuguese interests in Kerala. Hostilities were renewed when the Portuguese attempted to assassinate the Zamorin sometime between 1515 and 1518. In 1510, Afonso de Albuquerque defeated the Bijapur sultans with the help of Timayya, on behalf of the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire, leading to the establishment of a permanent settlement in Velha Goa (or Old Goa). The Southern Province, also known simply as Goa, was the headquarters of Portuguese India, and seat of the Portuguese viceroy who governed the Portuguese possessions in Asia.

The Portuguese acquired several territories from the Sultans of Gujarat: Daman (occupied 1531, formally ceded 1539); Salsette, Bombay, and Baçaim (occupied 1534); and Diu (ceded 1535).

.svg.png)

These possessions became the Northern Province of Portuguese India, which extended almost 100 km along the coast from Daman to Chaul, and in places 30–50 km inland. The province was ruled from the fortress-town of Baçaim. Bombay (present day Mumbai) was given to Britain in 1661 as part of the Portuguese Princess Catherine of Braganza's dowry to Charles II of England. Most of the Northern Province was lost to the Marathas in 1739, and Portugal acquired Dadra and Nagar Haveli in 1779.

Portuguese in Kerala- 1498 to 1660 Though the Portuguese were in Goa from 1530 till 1960, the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama first came to Calicut in 1498 and then shifted their base to Kochi and Kollam, where they ruled (or influenced the rule) and had their major presence for nearly 160 years changing the course of history in regard to politics, religion and trade in Kerala. From their base in Northern Kerala, they were able to defeat the Bijapur sultan. They finally shifted their capital to Goa in 1530.

In the 15th century, the Portuguese meddled in the church affairs of the Syrian Christians. The Udayamperoor Synod (1599) was the major attempt by the Portuguese Archbishop Menezes to Latinize the Syrian rite. Later in 1653, the Koonan Kurisu Sathyam (Coonan Cross Oath) led to the division of the local church into Syrian Catholics and Syrian Christians (jacobites).

The Dutch finally defeated the Portuguese in Kerala in the 1660 and pushed the Portuguese towards Goa,and the Daman, Diu colonies. Dutch influence in Kerala (Cochin and Kollam and Travancore) continued till 1741 when they were defeated by the Travancore King with the help of the British in the Battle of Colachel.

Portuguese on the Coromandel Coast. The Portuguese built the Pulicat fort in 1502, with the help of the Vijayanagar King. There were Portuguese settlements in and around Mylapore. The Luz Church in Mylapore, Madras (Chennai) was the first church that the Portuguese built in Madras in 1516. Later in 1522, the São Tomé church was built on the grave of Saint Thomas.

Thus there are Portuguese footprints all over the western and eastern coasts of India, though Goa became the capital of Portuguese Goa from 1530 onwards until the annexation of Goa proper and the entire Estado da Índia Portuguesa, and its merger with the Indian Union in 1961.

After India's independence

| Colonial India |

|||||

| Portuguese India | 1510–1961 | ||||

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 | ||||

| Danish India | 1696–1869 | ||||

| French India | 1759–1954 | ||||

| British India 1613–1947 |

|||||

| East India Company | 1612–1757 | ||||

| Company rule in India | 1757–1857 | ||||

| British Raj | 1858–1947 | ||||

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1867 | ||||

| Princely states | 1765–1947 | ||||

| Partition of India | 1947 | ||||

After India's independence from the British in 1947, Portugal refused to accede to India's request to relinquish control of its Indian possessions.

On 24 July 1954 an organisation called "The United Front of Goans" took control of the enclave of Dadra. The remaining territory of Nagar Haveli was liberated by the Azad Gomantak Dal on 2 August 1954.[5] The decision given by the International Court of Justice at The Hague, regarding access to Dadra and Nagar Haveli, was an impasse[6].

From 1954, peaceful Satyagrahis attempts from outside Goa at forcing the Portuguese to leave Goa were brutally suppressed.[7] Many revolts were quelled by the use of force and leaders eliminated or jailed. As a result, India closed its consulate (which had operated in Panjim since 1947) and imposed an economic embargo against the territories of Portuguese Goa. The Indian Government adopted a "wait and watch" attitude from 1955 to 1961 with numerous representations to the Portuguese Salazar regime and attempts to highlight the issue before the international community.[8]

Eventually, in December 1961, India militarily invaded Goa, Daman and Diu, where they were faced with insufficient Portuguese resistance.[9][10] Portuguese armed forces had been instructed to either defeat the invaders or die. Only meager resistance was offered due to the Portuguese army's poor firepower and size (only 3,300 men), against a fully-armed Indian force of over 30,000 with full air and naval support.[11][12]. The Governor of Portuguese India signed the Instrument of Surrender[13] on 19 December 1961. The territories were annexed by India.

Post-annexation

Status of the new territories

Dadra and Nagar Haveli existed as a de-facto independent entity from its liberation in 1954 until its merger with the Republic of India in 1961.

Following the annexation of Goa, Daman and Diu, the new territories became Union Territories within the Indian Union, now separately as Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Goa, Daman and Diu. Maj. Gen. K. P. Candeth was declared as military governor of Goa, Daman and Diu. Goa’s first general elections were held in 1963.

In 1967 a referendum was conducted where voters decided whether to merge Goa into the neighbouring state of Maharashtra. The anti-merger faction won, but full statehood was not conferred immediately. On 30 May 1987 Goa became the 25th state of the Indian Union. Daman and Diu was separated from Goa and continues to be administered as a Union territory.

The most drastic changes in Portuguese India after 1961 were the introduction of democratic elections, as well as the replacement of Portuguese with English as the general language of government and education. However the Indians allowed certain Portuguese institutions to continue unchanged. Amongst these were the land ownership system of the comunidade, where land was held by the community and was then leased out to individuals. The Indian government left the Portuguese civil code unchanged in Goa, with the result that Goa today remains the only state in India with a common civil code that does not depend on religion.

Citizenship

The Citizenship Act of 1955 granted the government of India the authority to define citizenship in the Indian union. In exercise of its powers, the government passed the Goa, Daman and Diu (Citizenship) Order, 1962 on 28 March 1962 conferring Indian citizenship on all persons born on or before 20 December 1961 in Goa, Daman and Diu.[14]

Indo-Portuguese relations

The Salazar regime in Portugal refused to recognize Indian sovereignty over the annexed territories, which continued to be represented in Portugal's National Assembly until 1974. Following the Carnation Revolution that year, the new government in Lisbon restored diplomatic relations with India, and recognized Indian sovereignty over Goa, Daman and Diu. Portugal continued to give the citizens of Portuguese India automatic citizenship. However, since 2006, this has been restricted to those born during Portuguese rule.

Postage stamps and postal history

Early postal history of the colony is obscure, but regular mail is known to have been exchanged with Lisbon from 1825 on. Portugal had a postal convention with Great Britain, so much mail was probably routed through Bombay and carried on British packets. Portuguese postmarks are known from 1854, when a post office was opened in Goa. An extraterritorial British post office in Damaun was open between 1854 and November, 1883. British Indian postage stamps were also available at the Portuguese post office at Goa from 1854 until 1877. A Portuguese post office opened at Diu in 1880[15].

The first postage stamps of Portuguese India were issued 1 October 1871 for local use[16]. These were issued for local use within the colony. Portugal had a postal convention with Great Britain, so mail was routed through Bombay and carried on British packets. Stamps of British India were required for overseas mail.

The design of the 1871 stamps simply consisted of a denomination in the center, with an oval band containing the inscriptions "SERVIÇO POSTAL" and "INDIA POST". In 1877, Portugal included India in its standard "crown" issue and from 1886 on, the pattern of regular stamp issues followed closely that of the other Portuguese colonies, the main exception being a series of surcharges in 1912 produced by perforating existing stamps vertically through the middle and overprinting a new value on each side.

The last regular issue was on 25 June 1960, for the 500th anniversary of the death of Prince Henry the Navigator. Stamps of India were first used 29 December 1961, although the old stamps were accepted until 5 January 1962. Portugal continued to issue stamps for the lost colony but none were offered for sale in the colony's post offices, and are thus not considered valid stamps.

Dual franking was tolerated from December 22, 1961 until January 4, 1962. Colonial (Portuguese) postmarks were tolerated until May 1962. Portuguese India stamps were available for sale up to December 28, thus the period up to January 4 was an attempt to use up stocks in private hands. After January 4, Portuguese India stamps were completely invalid or demonetised.

Outstanding stocks of charity tax stamps were overprinted for fiscal use, but not used. Portuguese India fiscals were overprinted in early 1962 in paisa and rupees and extensively used.

One of the prominent citizens from Panaji, Mr. Carvalho created several combination covers, using low face value definitives of Union of India and Portuguese India, on each of the days up to January 4 including Christmas Day 1961. Most were readdressed to his daughter in pen. Due to the absence of back-stamps or arrival CDSs, it's unlikely any of these went through the mail. Several unaddressed envelopes are to be found with similar combinations of Portuguese India and Union of India stamps in this time frame. The challenge being to obtain a postmark from each of the different days. Obtaining covers from late January to May 1962 with Portuguese India postmarks has proved to be quite difficult. These covers are scarce, but don't command high prices, which is good for the collector not for the speculator. Much more scarce are the Prisoner Of War (PoW) covers sent by Portuguese civilian internees from Goa to Portugal between late December 1961 and March 1962. These were free franked covers with appropriate markings and command a high premium.

Portuguese India philately started with combination covers (British India) and ended with combination covers (Sovereign India).

See also

- Estado Novo (Portugal)

- List of colonial heads of Portuguese India

- Portuguese Indian Rupia

- Portuguese Indian Escudo

- Goa liberation movement

- Portuguese Goa State

References

- ↑ Narayanan.M.G.S., Calicut: The City of Truth(2006) Calicut University Publications

- ↑ The incident is mentioned by Camoes in The Lusiads wherein it is stated that the Zamorin "showed no signs of treachery" and that "on the other hand, Gama's conduct in carrying off the five men he had entrapped on board his ships is indefensible".

- ↑ Sreedhara Menon.A, A Survey of Kerala History(1967),p.152. D.C.Books Kottayam

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Malabar manual by William Logan p.312

- ↑ Goa's Freedom Movement

- ↑ International Court of Justice Case Summaries, Case Concerning Right of Passage Over Indian Territory (Merits), Judgment of 12 April 1960

- ↑ Rear Admiral Satyindra Singh AVSM (Ret.), Blueprint to Bluewater, The Indian Navy, 1951-65

- ↑ Lambert Mascarenhas, "Goa's Freedom Movement," excerpted from Henry Scholberg, Archana Ashok Kakodkar and Carmo Azevedo, Bibliography of Goa and the Portuguese in India New Delhi, Promilla (1982)

- ↑ Government Polytechnic of Goa, "Liberation of Goa"

- ↑ ' "The Liberation of Goa: 1961" Bharat Rakshak, a Consortium of Indian Military Websites,'

- ↑ Jagan Pillarisetti, "The Liberation of Goa: 1961" Bharat Rakshak, a Consortium of Indian Military Websites

- ↑ Liberation of Goa, Maps of India

- ↑ http://www.shvoong.com/books/469174-dossier-goa-recusa-sacrif%C3%ADcio-in%C3%BAtil/

- ↑ "Gangadhar Yashwant Bhandare vs Erasmo Jesus De Sequiria". manupatra. http://www.manupatrainternational.in/supremecourt/1950-1979/sc1975/s750288.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ↑ Robson Lowe, Encyclopedia of British Empire Postage Stamps, v.III, London (1951), p. 288

- ↑ Gilbert Harrison and Lt. Francis H. Napier, Portuguese India, with Notes and Publishers' Prices Stanley Gibbons Philatelic Handbooks, London (1893)

External links

- The GoaMog Information Resource Portal

- Goacom

- Summary of the judgment of the International Court of Justice in the Right of Passage over Indian Territory (Portugal vs. India) case

- Dutch Portuguese Colonial History Dutch Portuguese Colonial History: history of the Portuguese and the Dutch in Ceylon, India, Malacca, Bengal, Formosa, Africa, Brazil. Language Heritage, lists of remains, maps.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)